- Home

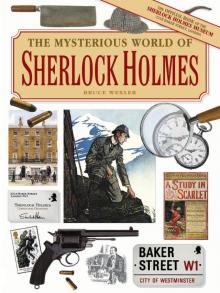

- Bruce Wexler

The Mysterious World of Sherlock Holmes

The Mysterious World of Sherlock Holmes Read online

Copyright © 2007 Colin Gower Enterprises Ltd.

First Skyhorse Publishing edition, 2020

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or [email protected].

Skyhorse® and Skyhorse Publishing® are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc.®, a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

Print ISBN: 978-1-5107-4960-3

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-5107-4961-0

Printed in China

Contents

CHAPTER ONE

Dr. Arthur Conan Ignatius Doyle: An Author’s Life

CHAPTER TWO

Sherlock Holmes: A Life in Print

CHAPTER THREE

Sherlock Holmes in “The Great Wilderness”

CHAPTER FOUR

Medical and Forensic Science in the Sherlock Holmes Stories

CHAPTER FIVE

Sherlock Holmes and the Law

CHAPTER SIX

Sherlock Holmes’s Women

SPECIAL FEATURE

The Traveling Detective

CHAPTER SEVEN

Sherlock Holmes Today

SPECIAL FEATURE

Sherlock Holmes Paraphernalia

SPECIAL FEATURE

Sherlock Holmes Pub

CHAPTER EIGHT

Sherlock Holmes on Stage, Screen, and Radio

The Canon in Alphabetical order

CHAPTER ONE

Dr. Arthur Conan Ignatius Doyle: An Author’s Life

Sure there are times when one cries with acidity

“Where are the limits of human stupidity?”

Here is a critic who says as a platitude

That I am guilty because “in gratitude

Sherlock, the sleuth-hound, with motives ulterior,

Sneers at Poe’s Dupin as ‘Very inferior.’”

Have you not learned, my esteemed communicator,

That the created is not the creator?

As the creator I’ve praised to satiety

Poe’s Monsieur Dupin, his skill and variety,

And have admitted that in my detective work

I owe to my model a deal of selective work.

But is it not on the verge of inanity

To put down to me my creation’s crude vanity?

He, the created, would scoff and sneer,

Where I, the creator, would bow and revere.

So please grip this fact with your cerebral tentacle:

The doll and its maker are never identical.

ARTHUR CONAN DOYLE, 1912

It was the evening of Monday, November 26, 1894. The house lights were dimmed in Toronto’s Massey Hall and there was a palpable aura of excitement and high expectation as the speaker climbed to stand behind a high desk, drenched by a single point of light. He was certainly physically impressive, “A giant in size. He looks to be about six feet four and is not at all slim” reported the Toronto Star. The paper went on to be somewhat critical of the speaker’s declamatory style, and imply that if he had been lecturing on any other subject “he would not have been so entertaining.” Fortunately, however, the speaker’s subject was one that has been found continually fascinating for over 120 years, since A Study in Scarlet first appeared in Beeton’s Christmas Annual for 1887. The speaker was none other than Arthur Conan Doyle, and his subject was his own creation, possibly the most recognizable fictional character ever conceived, and the world’s first consulting detective: none other than the redoubtable Sherlock Holmes.

Conan Doyle lectured at Toronto’s Massey Hall.

Considering that the Toronto audience was full of Holmes aficionados, ready to hang on Conan Doyle’s every word concerning the great detective, the tenor of Doyle’s lecture was rather strange. He was at pains to convince his audience that, not only was Holmes “no more,” but that he “would not be resurrected.” According to the Toronto Star reporter, the author maintained that his personal literary interest was in writing “bright pictures of chivalry and deeds of daring like those in which Scott won his fame.” Conan Doyle’s literary canon does indeed contain many works of historical fiction, but these have substantially withered away from disregard. Conan Doyle continued his address by further distancing himself from his famous creation, whom he dismissed as his “doll.” The author also maintained that, far from having any ability to solve mysterious crimes himself, Holmes was actually far from being sharp, and had only the ability to “put himself in the position of a shrewd man and imagine what the shrewd man would do.”

Conan Doyle’s most famous creation had actually already been sent to his demise. The Strand had published “The Final Problem,” the last story in the second series of Holmes stories, in December 1893, and for all his readers knew, the great man had fallen at Reichenbach never to return. (In novel form, these stories were published as The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes). A chance visit to the Reichenbach Falls in Switzerland had presented Conan Doyle with an irresistible idea for Holmes’s demise, and he was quick to grasp it. He was already sick of writing about Holmes. The adventures of his famous detective tortured him with the constant need for plotting, devising, counter-plotting, and resolution. He wanted to exorcize himself of his wearisome creation, and had written to his mother “I am in the middle of the last Holmes story, after which the gentleman vanishes never to return! I am weary of his name.” He did this even in the full knowledge of the financial implications for him and his family, “I must save my mind for better things… even if it means I must bury my pocketbook with him.” Conan Doyle planned to abandon the Holmes series as early as 1891, when he confessed, “I have had such an overdose of [Holmes] that I feel towards him as I do toward pate de foie gras, of which I once ate too much, so that the name of it gives me a sickly feeling to this day.” It seems that, at this point at least, author and character were in accord. As Holmes writes in a note discovered (after his cryptic disappearance) by his faithful associate Watson, “my career had in any case reached its crisis, and no possible conclusion to it could be more congenial to me than this.”

Apart from reading from a variety of his own work, the balance of Conan Doyle’s lecture was largely autobiographical. He sketched his own literary career, which supposedly began when the great novelist William Thackeray took the juvenile Arthur Conan Doyle onto his lap. He subsequently wrote his first story at the age of six: an illustrated work that concentrated on men and tigers.

Sidney Paget’s famous illustration of Holmes’s untimely demise at the Reichenbach Falls, engineered by Conan Doyle in 1893. The scene was inspired by the author’s travels in Switzerland.

In fact, Conan Doyle’s artistic ability was deeply ingrained in his family heritage. His grandfather was the renowned caricaturist John Doyle. Born in 1797 into an impoverished Roman Catholic family in Dublin, Ireland, John Doyle had attempted to earn a living as a portrait painter, but had been forced to immigrate to London (in 1821) in an attempt to further his career. Although he exhibited at the prestigious Royal Acad

emy, Doyle had failed to turn this to commercial advantage and he turned to lithography instead. Cartoons were hugely popular at this time, and his work regularly appeared in the Times for over twenty years (identified by the monogram H. B.). Doyle was well known to his great contemporary, novelist William Thackeray, who described his cartoons as “polite points of wit, which strike one as exceedingly clever and pretty, and cause one to smile in a quiet, gentlemanly kind of way.” His work was in sharp contrast to fellow cartoonists James Gillray and Thomas Rowlandson, whose pens dripped with caustic satire.

A political cartoon by Conan Doyle’s grand-father, John Doyle.

The author’s birthplace in Edinburgh, Scotland.

John Doyle died in 1868, but two of his sons, Richard and Charles, continued the family’s artistic tradition. Richard was a cartoonist. Charles was also an accomplished artist who painted, illustrated books, and worked as a sketch artist at criminal trials. Unfortunately, whereas Richard made a good living illustrating fairy stories and Charles Dickens’s Christmas books for Punch magazine, Charles proved to be the only Doyle who was unable to turn his undoubted talent into a steady income. Despite this, his son, Conan Doyle, always considered his father to be the most gifted artist in the family. Charles married the accomplished Mary Foley on July 31, 1855. He had met her at her widowed mother’s Edinburgh boarding house, having relocated to the city from England in 1849 to take up a post in Her Majesty’s office of Works. Although the marriage proved to be disastrous, as Charles fell prey to depression, drink, and epilepsy, the couple produced ten children. Seven survived to adulthood. Their second child and eldest son, Arthur, was born at the family home, 11 Picardy Place, Edinburgh, on May 22, 1859. From the very beginning, Mary was the chief cultural and emotional influence on her son’s life. In particular, Mary told her son “vivid stories” that he was to remember all his life. Conan Doyle’s second wife, Jean, described Mary as a “very remarkable and highly cultural woman. She had a dominant personality, wrapped up in the most charming womanly exterior.”

Arthur Conan Doyle as a young boy with his father Charles.

When Arthur reached the age of nine in 1868, his more prosperous relatives decided to send him to Hodder, the preparatory school for the Jesuit College at Stonyhurst. He entered the upper school in 1870 and was to spend five years there. Located in the Ribble Valley in Lancashire, the school was part of the English public school system, and was notorious for its stern regime and harsh corporal punishment. Doyle’s time at the school was largely miserable. But there were some positive outcomes. The first was lifelong correspondence with his mother, “the Ma’am,” which he began while at school. The second was a lifelong interest in sports and sportsmanship. His cricketing abilities were particularly renowned. The third were some colorful characters that later appeared in his fiction: he met two Moriartys at Stonyhurst.

Arthur matriculated from Stonyhurst with honors in 1875, and spent the following year at the Jesuit school at Feldkirch in Austria. Unfortunately, this exciting time coincided with his father’s dismissal from the civil service in 1876. By the time Arthur left school, his father’s mental health had deteriorated so seriously that one of his first grim tasks as an adult was to co-sign papers to commit Charles Doyle. Doyle had initially been sent to Fourdoun House, a nursing home that specialized in the treatment of alcoholics. But a violent escape attempt had resulted in his committal to the Montrose Royal Lunatic Asylum. Charles was to remain institutionalized until his death in 1893.

Conan Doyle spent five years at Stonyhurst, a traditional English public school.

Edinburgh University’s prestigious medical school, as it was in Victorian times when Doyle studied there.

Charles’s departure ushered in a different way of living for the family. Forced to take in lodgers to make ends meet, Mary Doyle had met medical man and pathologist Dr. Bryan Charles Waller. In effect, Waller became Mary’s unacknowledged partner, and in 1883, she moved to the Waller family estate in Yorkshire with one of her daughters. She was to live there, rent free, for decades. Waller also became highly influential in Conan Doyle’s life, and the young man decided to abandon the Doyle family’s artistic tradition to train as a doctor. He duly enrolled at Edinburgh University’s prestigious Medical School with Waller’s moral and financial support. Ironically, Conan Doyle met two other men who were to become famous literary figures at the University, James Barrie, and Robert Louis Stephenson. It was dur ing his university career that Conan Doyle first saw his work in print. His first published short story, “The Mystery of Sasassa Valley,” appeared in the Edinburgh magazine Chamber’s Journal in 1879, while (in complete contrast), the British Medical Journal published his paper “Gelseminum as a Poison” in the same year.

Dr. Joseph Bell lectured at the medical school and provided Conan Doyle with much of the inspiration he needed to create Holmes.

Conan Doyle’s most significant university experience, however, was his 1876 meeting with Dr. Joseph Bell. Famous for his brilliant and original lectures, Bell was also Queen Victoria’s personal surgeon during her frequent visits to Scotland. His intellectual approach to gathering circumstantial evidence to make astonishingly accurate medical diagnoses was inspirational. The professor applied the “trained use of observation” to assess his patients, gathering hoards of seemingly trivial information to create a meaningful picture of the whole person. Remind you of anyone? Conan Doyle became one of Bell’s favored students, and during his second year at medical school, he was Bell’s clerk at the Royal Infirmary’s open clinic. Over a century later, the Conan Doyle/Bell relationship was immortalized in a series of books by David Pirie, which was filmed for television as The Murder Rooms. Conan Doyle was fully conscious of his debt to Bell’s forensic detective work and wrote, “It is to you that I owe Sherlock Holmes.” Mutual acquaintance Rudyard Kipling asked of Holmes, “Could this be my old friend, Dr. Joe?” But Holmes was not simply a pastiche of Bell’s flamboyant personality. Doyle acknowledged that he derived aspects of the character from several other sources (“I owe to my model a deal of selective work”), including Edgar Allan Poe’s detective character, Monsieur C. Auguste Dupin, together with the infamous Eugene Francois Vidocq. Vidocq was a reformed master criminal who became the first chief of the Surete in Paris. The “detective” writing style of both Charles Dickens and Wilkie Collins is also apparent in Conan Doyle’s Sherlockian works. Throughout his student days, Conan Doyle read voraciously, including William Thackeray’s Esmond, George Meredith’s Richard Feverel, and Washington Irving’s Conquest in Granada.

The statue of Sherlock Holmes erected in Edinburgh to honor Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

A whaling boat on which Conan Doyle served as a medical officer. His handwritten log of the voyage has survived.

The creation of Holmes was still years ahead. In 1881, Conan Doyle graduated as a Bachelor of Medicine and Master of Surgery. In his third year at Edinburgh, the young medic had served as a ship’s doctor on a whaling boat, The Hope. On graduation, his first job was as the medical officer on the Liverpool steamer Mayumba. While Doyle had hugely enjoyed his time aboard The Hope in the freezing Arctic, he hated the dirt and heat of Africa and became seriously ill from a tropical fever. He resigned his place as soon as the ship re-docked in England. His next medical foray was to Plymouth (in 1882), to work as a doctor in practice with his former schoolmate, George Budd. But Conan Doyle became increasingly concerned about Budd’s ethical standards, and their relationship fell apart in a few weeks, when Conan Doyle left the practice. He was in serious financial trouble, on the verge of bankruptcy. He moved to Southsea, Portsmouth to open his own practice. It was a fairly shoestring operation, as he could only afford to furnish the consulting rooms. Business was initially slow, which gave Arthur the chance to compose stories in between his rather sparse patients. A small flurry of short stories appeared, including “The Captain of the Polestar,” “J. Habakuk Jephson’s Statement,” “The Heiress of Glenmahowley,” “The Cab

man’s Story,” and “The Man from Archangel.” These were published in various magazines, including Cornhill Magazine, Cassell’s Saturday Journal, and Temple Bar.

Conan Doyle photographed outside Bush Villa in Southsea, England where he set up medical practice in the mid 1880s.

Conan Doyle’s brass nameplate from Bush Villa, which he kept as a souvenir after he became a famous writer.

Conan Doyle also found time to get married during this period. He met Louise Hawkins (“Touie”) in 1885 and married her in August of that year. The Ma’am highly approved of her son’s choice. Touie was a home-loving woman, attractive rather than beautiful. Doyle described her as “gentle and amiable.” 1885 also saw the publication of Conan’s Doyle doctoral theses on the effects of syphilis, “An Essay Upon the Vasometer Changes in Tabes Dorsalis.”

Ironically, Conan Doyle had met Touie through the sickness of her brother, John Hawkins. Hawkins had been a resident patient of Conan Doyle’s at his Southsea villa, but had died of cerebral meningitis in 1885. Hawkins’s death, and the subsequent marriage of his sister (and heir) to his doctor led to a great deal of local gossip. Worse was to follow. A poison pen letter about Hawkins’s sudden death, and the rather hasty burial that Conan Doyle had arranged, was sent to the police. This almost resulted in an official enquiry into Hawkin’s “suspicious death,” and only the supportive intervention of Conan Doyle’s medical neighbor averted police involvement. Perhaps this horribly close brush with the legal system explains Conan Doyle’s interest in miscarriages of justice. Biographer Peter Costello describes Conan Doyle’s shock realization of the “narrow margin of fate that protects the innocent, the minor twist of evidence that could acquit or hang an accused.”

The Mysterious World of Sherlock Holmes

The Mysterious World of Sherlock Holmes